Due to conservation efforts, wildlife is returning to Europe, and this is clearly challenging our current way of living and thinking about nature and our place in it. We are not used to seeing a wolf in our backyard or walking across the street. We have forgotten that wolves are an essential part of European ecosystems due to nature amnesia.

This article is written by Fedra Herman, the author of The Wandering Biologist Blog. Fedra is an MSc of Conservation Biology graduate from The University of Queensland, passionate about rewilding and nature restoration. As a member of the European Young Rewilder’s Communications Team, she hopes to help spread knowledge about rewilding and inspire others to restore, protect, and cherish our planet’s ecosystems.

In recent years, we have heard many “doom and gloom” stories about environmental issues. Deforestation, coral bleaching and species extinctions are some of the topics that seem to appear everywhere. As a conservation biology student, I get confronted with the degradation of the natural world daily. Such news is disheartening, and many people, including me, are overwhelmed by the vastness of those problems.

These devastating stories of loss are constantly highlighted in the news and often overshadow any positive news on the state of our natural world. When we focus on the bad, it is easy to lose hope and think that conservation actions are useless and don’t lead to anything. But this is far from the truth!

Coexisting with Wolves

An inspiring conservation success story is that of the European Grey Wolf and its return to Western Europe. During the 19th century, the grey wolf disappeared in most parts of Europe, due to human pressures, e.g. hunting and habitat loss. However, in recent years, grey wolves are once again growing in numbers and have returned to the French, Swiss and Austrian Alps [1]. They even made it all the way to East Germany, sometimes crossing the border to the Netherlands. In Belgium, the first wolf sighting dates from 2011 [2].

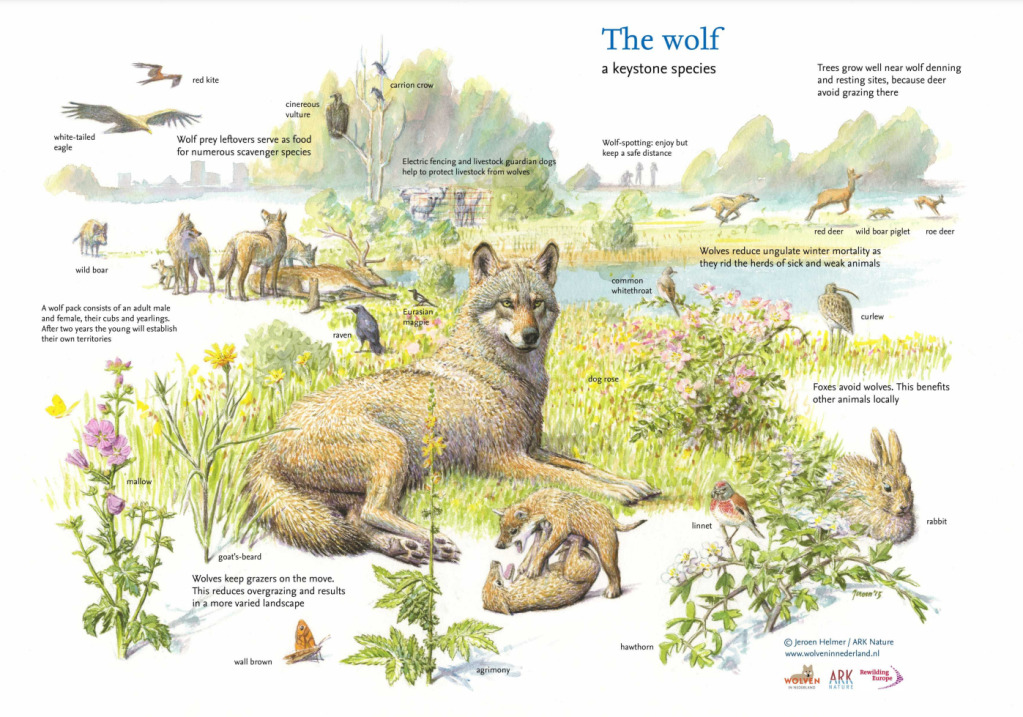

Wildlife comebacks such as these show that when we protect a species, give it the space it requires and restore the connectivity of its habitat, it can return. When I learned about rewilding for the first time, I got excited: I could already see a much greener and more biodiverse future. The regulating effect of wolves on grazers, such as deer, brings with it numerous positive benefits [6, 7]. The mere presence of top predators in a landscape can result in an increase in biodiversity and its resilience [3, 4].

However, not everyone is aware of the positive trophic interactions related to the presence of these animals and, thereby, don’t realise why the return of the wolf is a positive thing. Many people don’t get excited about the prospect of living alongside wolves.

It must be acknowledged that this can be a challenge, especially if you are a farmer who has lost a valuable animal to this top predator. But all across the globe, there are examples of communities living in harmony alongside wolves and other predators. So, with the right measures and compensation schemes in place, it is possible.

Nonetheless, in 2019, the first (and only) wolf pack in Flanders, northern Belgium, was killed on purpose by hunters, a severe crime since the wolf is a legally protected species in both Europe and Flanders [5].

Our Opinion Matters

In a Dutch podcast episode by EOS Wetenschap, random people on a market in East Flanders were asked their opinion on the return of wildlife to their country. Here are some of the answers (which I translated from Dutch to English) that the interviewer received:

- “I believe we have to learn how to live with nature. When nature changes, humans have to adapt as well.”

- “The return of the wolf shows that nature is getting better. I think this is positive.”

- “Every animal has the right to live.”

From these answers, you would think that people in Belgium are welcoming the wolf with open arms. But alas, not everyone has the same opinion on this topic:

- “We don’t have space, there are buildings everywhere.”

- “I think this would be very hard for farmers.”

- “Wolves will eat our pets.”

- “The wolf should not be allowed.”

- “Because of the wolf, you can’t keep any small animals and chickens.”

- “Reintroducing wolves is not an option since there simply is no space. I believe that some people are planning to reintroduce them anyway.”

A couple of months ago, I attended a webinar by Dr Martin Drenthen, an associate professor of philosophy at Radboud University. During his lecture, Dr Drenthen gave some examples of the opinions of people on the comeback of wolves to The Netherlands:

- “If wolves would stay in natural areas, I would have nothing against them.”

- “Wolves belong in the wilderness.”

- “I would like to live together with the wolf, but it is simply impossible.”

- “The wolf has been introduced by humans or escaped from a zoo.”

- “That wolf is a hybrid, natural wolves would never come this close to humans.” (A response to the sighting of a wolf in a busy street in The Netherlands.)

- “Wolves belong in nature. We have no real nature, so, the wolf does not belong here. They are intruders.”

Many people believe that the wolf has been reintroduced on purpose by nature conservationists in Belgium and The Netherlands and that the presence of wolves is “unnatural” in these two countries. Of course, the comeback of the wolf is an example of passive rewilding. It is a natural consequence of the legal protection this species now receives, and the restoration of the connectivity of its habitat.

Another popular opinion is that there simply is no place for wolves in a country such as Belgium or The Netherlands. “The wolf is an intruder” and “It belongs in nature” are common answers. But how can the wolf be an intruder if the animals simply return to parts of the world where they used to occur before? You might agree that wolves belong in nature. But where does nature start (and end)?

Some think that wolves, and other “wild” animals, only belong in enclosures in zoos or nature reserves. We see our societies as separate from “nature”. There is a disconnection between humans and nature, a nature-culture dichotomy. Instead of seeing ourselves as a part of nature, we see it as a place that can be visited.

“Nature is not a place to visit. It is a home.” – GARY SNYDER

We like to place nature and wilderness behind a border. When we restore and rewild areas we fence them off to prevent wild cattle and horses from invading “our space”. But can we really separate nature from where we live?

Human Rewilding

Due to conservation efforts, wildlife is returning to Europe, and this is clearly challenging our current way of living and thinking about nature and our place in it. We are not used to seeing a wolf in our backyard or walking across the street. We have forgotten that wolves are an essential part of European ecosystems due to nature amnesia.

The need for human-wildlife coexistence is more urgent than ever and the way we think about the return of wildlife matters. To successfully co-exist with wildlife, we must not only rewild nature but also ourselves.

I believe that we cannot divide the world into nature reserves and cultural landscapes. We need to realise that we share this world with other creatures and need to relearn how to live alongside them. But, are we prepared to make room for the very beings we chose to protect from going extinct?

Resources

[1] Drenthen, Martin. (2015). The return of the wild in the Anthropocene. Wolf resurgence in the Netherlands. Ethics, Policy & Environment. 18. 318-337. 10.1080/21550085.2015.1111615.

[2] Agentschap Voor Natuur En Bos. (2023). De wolf in Vlaanderen. Retrieved from https://www.natuurenbos.be/de-wolf-in-vlaanderen

[3] Letnic, M., Ritchie, E. G., & Dickman, C. R. (2012). Top predators as biodiversity regulators: the dingo Canis lupus dingo as a case study. Biological Reviews, 87(2), 390-413.ISO 690

[4] Ritchie, E. G., & Johnson, C. N. (2009). Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation. Ecology letters, 12(9), 982-998.ISO 690

[5] Jacobs, A. & Vercayie, D. (2019). Wolvin Naya is dood. En wat nu?. Natuurpunt website. Retrieved from https://www.natuurpunt.be/nieuws/wolvin-naya-dood-en-wat-nu-20190930

[6] Raynor, J. L., Grainger, C. A., & Parker, D. P. (2021). Wolves make roadways safer, generating large economic returns to predator conservation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(22), e2023251118.

[7] Macdonald, B. (2022). Chapter 8: Lynx and Wolves. In Cornerstones: Wild forces that can change our world. Bloomsbury Publishing.