This blog is written by Dutch artist and nature enthusiast Myrthe Majoor. With her short animated films, she inspires others to think about their relationship with nature. Myrthe loves learning about the natural world and enjoys talking about its intricacies with others. She sees the spreading of knowledge and our connection with nature as key elements in nature conservation, which is why she focuses on both in her art.

Hi! My name is Myrthe Majoor and I’m a Dutch animation filmmaker and illustrator. About half a year ago, I joined the European Young Rewilders, all because of my current film production. ‘How did you get from animation to rewilding?’, you might think. Well, let me tell you!

It all started with the idea to make an animated short film about muskoxen, back in 2021.

If I’m honest, I did not know anything about muskoxen, but I just had a feeling there was something to be found in them. I couldn’t have been more right.

Without further ado, I planned a research trip to study the muskoxen in Dovrefjell, Norway, and started my journey with my boyfriend Denys at the end of May 2022. We were surprised by the stunning valleys and snow-capped mountains of Dovrefjell and surrounding areas.

I had not looked into the habitat of the Norwegian muskoxen beforehand, as I wanted to wait and see the real thing with my own eyes. Honestly, that was just the best decision. The landscape left me in awe and I could not wait to find the muskoxen in this beauty.

Denys and I left our car where the road ended, late in the evening, and hiked an hour into Åmotsdalen, a river valley where a cabin waited for us, totally off the grid. We arrived shortly before midnight. The familiar darkness of the night never arrived, as the sun never really disappears behind the horizon in Scandinavia during the warmer months. The cold had rolled in, so we made ourselves comfortable. We got our water from the closest stream and cooked our first meal on top of a little wood stove, with which we heated the small cabin directly as well. The ants loved the warmth as much as we did and they shared the dining table with us, with the temperatures outside a little below 0 degrees Celsius.

The morning after, we rose early to meet our guide for the day, biologist Per Henrik Rishøi. The three of us entered Dovrefjell and it did not take us long before we spotted two lone muskox bulls. Per taught me about the history of the area, the animals and plants in the ecosystem, the things to keep an eye on in muskox body language when spotting one, and much more. We paused to look at a white-tailed eagle peacefully floating past, ravens in the distance and falcons building a nest. We found remains of a red fox and a reindeer or sheep, saw many droppings from muskox and willow grouse, and admired a bluethroat calling from the top of a tree. We ended up seeing more muskoxen further into the area, a mother and her two calves from last year.

On our way back, we spotted a lone muskox cow in between the trees. We carefully and slowly approached her, with Per pointing out what to look for to know if the situation was safe or not. Muskoxen can be dangerous when you ignore their sense of personal space. With enough respect, a muskox tolerates your presence. When there’s calves around, though, a lot of distance is advised, as the cows get very aggressive when it comes down to protecting their young. In general, a distance of 200 metres is advised for your own safety and to prevent the muskox from growing stressed.

The muskox cow that we had approached, had noticed us in our chosen observation spot and stared at us with a fierce look in her eyes, before rubbing her horns against the willow bushes – a clear warning sign. Per immediately told us to back up a bit, and as soon as we did, the cow relaxed, resumed foraging and lay down. After a little while of sharing space with this special animal, we silently left the resting muskox and concluded our first day with Per. Filled with knowledge and experiences, we made our way back to the cabin.

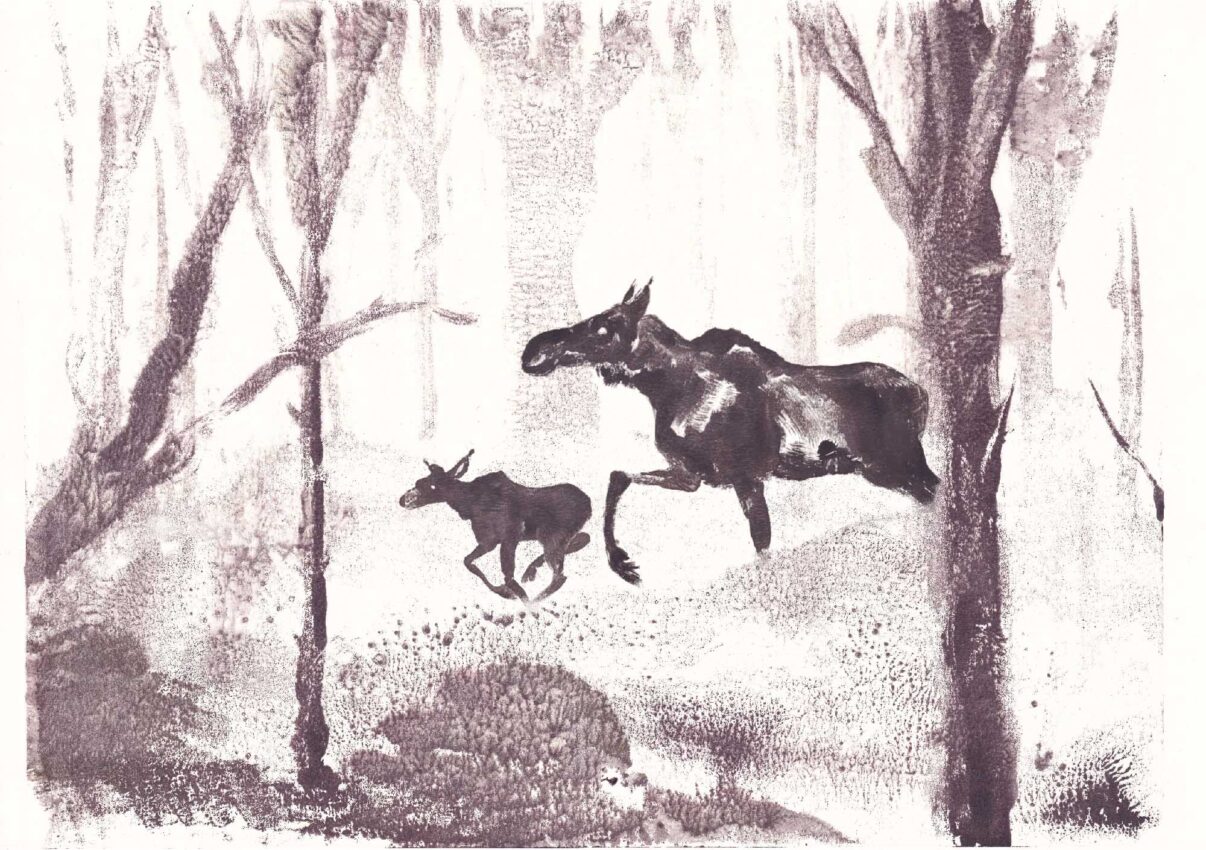

In the days that followed, Denys and I went out into different parts of the area and I studied the natural landscape with its plants, animals, ecosystems and sounds. We found a possible wolverine burrow at a distant mountain side, saw many more muskoxen, heard golden plovers announce our presence in the valleys and went up into nature. We found tracks in the snow that belong to the Eurasian lynx and saw moose with a young in the marshes late at night.

After travelling home, I realised I had found something that I did not know I was missing. Being humbled by the vastness of the mountain range, by not seeing humans for days, by finding a rest and peace I had never known. I had found my true home: wild nature.

Beside this, I now had a clear idea of what I wanted my film to be about: the relationship between man and nature.

In 2023, I returned to Dovrefjell and the muskoxen to finish my research, together with Denys and two artist friends. I had read into and documented the gathered knowledge and made a list of the missing links I wanted to find before I started my film production. I found the muskoxen again, with this time even several calves that were only a few weeks old. I saw many moose among which a piebald bull, polar fox burrows, red foxes, climbed mountains, recorded birds, the wind, sounds of nature.

A side trip took me to Funasfjällen, Sweden, where a small wild herd of muskoxen lives in the forests. The Muskox Centre in Tännas works on improving the gene pool of the wild muskoxen, teaching visitors about these beautiful animals and keeping the muskoxen as wild as possible in their centre. The Muskox Centre arranged for me to record sounds made by their muskoxen. For this, I was allowed to get closer than most visitors, but of course still from behind a fence and with respect for the personal space of their muskoxen. I made sure to show in my body language that I respected them, and that I would back away if they wanted me to. Muskox Brusa indeed showed a feeling of unease at the beginning, so I took some more distance and she relaxed. My presence was accepted and for the first time, I had the chance to study muskox movements and behaviour from up close. It was fascinating, and I recorded some useful sounds.

Jonas from the Muskox Centre took us up the mountain and pointed out the surrounding areas in the beautiful views, showing where the wild muskoxen roamed, where one had a good chance to see brown bears or moose, etcetera. We did not see the bears, but I did find old bear scat in a blueberry field on a small solo hike the next morning.

I saw many beautiful things and found my home once again.

After returning to the Netherlands with my notes, photos, videos, sound recordings, collected bones, antlers and bits of dried vegetation, I started the preparations for my production. I contacted Per when I had additional questions and reached out to Rewilding Europe, as I had some questions regarding the rewilding process of an area like Dovrefjell. My film touches upon the rewilding of such an ecosystem, so I got on the phone with Staffan Widstrand and learned more about the role of the muskox in the ecosystem, about the current alarming states of certain aspects of ecosystems like Dovrefjell, about consequences of negative and positive changes in the landscape, and more. It was a very inspiring call and I learned exactly what I needed to know.

I learned that the role that the muskox plays echoes through in multiple layers of the ecosystem. As a big grazer, the muskox keeps the vegetation low, like the willow bushes that can be seen in the photo above. By doing so, space is created for low growth plants and organisms like reindeer lichen, on which the threatened mountain reindeer are largely dependent in the winter. Beside this, the grazing of big grazers creates a landscape with low vegetation and low grass, from which rodents like lemmings profit. Then again, there are many other animals like polar foxes and birds of prey that profit from a healthy rodent population. Every life supports another life.

Another important fact is that the migration patterns of muskoxen and mountain reindeer compliment each other. Muskoxen spend the summers in the valleys, trimming the willow bushes and other vegetation, stimulating the growth of – among other things – reindeer lichen, as explained before. In the winter, the mountain reindeer stay in the valleys, searching for food – mostly reindeer lichen – underneath the thick layer of snow.

During winter, the muskoxen can be found in higher altitudes, where wind keeps the layers of snow thinner, which makes foraging in the harsh winters easier for them. Mountain reindeer on the other hand, spend the summers in the higher altitudes, where the mosquitos don’t disturb them when they forage and when food is abundant in low and high altitudes.

Not only do muskoxen support wild reindeer food resources, the complimentary migration patterns also means that dung from big grazers can be found in both lower and higher altitudes of the landscape all year round, supporting numerous insects, plants and other organisms.

Another part of the role of the muskox in its ecosystem, is the fact that the muskoxen trample the ground. Some species of plants grow best on trampled ground, and certain birds like to breed on it. I came across such a small musk ox plateau of trampled ground, offering an open space of sandy soil amidst a landscape tightly grown by bushes, lichens and mosses that offer little to no actual open space without vegetation. Truly special to see!

Last but not least, when big grazers like the muskox die, their carcass is a source of life for many life forms, from microbes to insects, from rodents to foxes, and from ravens to wolverines. A carcass provides its surroundings with fat, meat, calcium and nutrients.

As you can see, the muskox plays a very important role in its ecosystem, supporting soil nourishment, microbes, lichens, plants, insects, rodents, polar foxes, mountain reindeer, wolverines, lynx, bears, wolves, gyrfalcons and much more.

In short, muskoxen support the existence of a healthy biodiversity within their ecosystem.

After my call with Staffan, I researched the topic of rewilding some more and looked into the youth organisation of Rewilding Europe, the European Young Rewilders. After looking at their website, I knew this was an inspiring network and decided to join the group. I am very glad to have done so and got to know many interesting people. There is so much to learn from each other, and there is power in standing together for the things you love.

With my animated short film Home of the Giants, I ask people to ponder on their relationship with the natural world and their impact on it, and I strive for the protection of wild nature, for the protection of my home.

If you’re interested to learn more about my animated short film about Dovrefjell and the muskoxen, make sure to follow my Instagram page and check out my crowdfunding campaign with which I am raising the funds to finish and launch my film.

All help with funding or spreading the word is highly appreciated!

As you now know, a small idea for an animated film can lead to so many beautiful things.

To art, to finding your home in nature, and to finding the wonderful EYR community.

It’s been a journey for sure, and I can’t wait to find out what the future brings!